Popularity of ‘fast furniture’ creates an environmental problem of huge proportions

Thank goodness that Home News Now is a digital publication because I wouldn’t want to be responsible for killing trees for this particular column. This week, we’re looking at the planet’s landfills and the volume of disposable furniture going into these landfills as an indirect result of the pandemic.

A spooky story from the New York Times that published on Halloween has since been “trending” in global news media, a story chronicling the troubling, even “Leviathan” quantity of “fast furniture,” as the report terms it, finding its way into landfills and trash bins around the world.

The news here, then, relates to both the implied ethical implication of producing furniture meant to last five years or so and the environmental harm that life span implies, and that this post-pandemic spin on this particular business model has traveled the world. As a news meme, it’s made stops in, among other places, Spain, the Philippines, India and Ireland.

The Times mentioned Ikea, Wayfair and Overstock as leading purveyors of this so-called “fast furniture,” a term that connotes McDonald’s or Taco Bell, or, as the Times writer describes it, “the one-season fling of furnishings.” The pandemic spurred one of these seasons, sending the newly remote labor force to the internet for home office furniture – desks and tables, bookcases, nightstands and chairs. Lots of chairs.

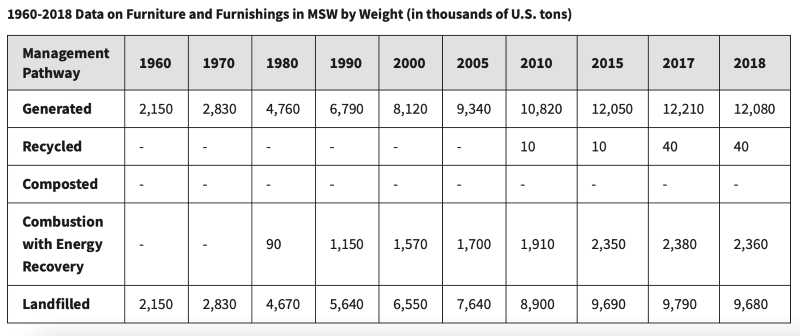

Even before the pandemic, the furniture flow into landfills soared. Nearly 10 million tons of furniture poured into U.S. landfills in 2018, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, part of a 450% increase in solid waste in this country since the 1960s. For that same year, 2018, only 40,000 tons of furnishings were recycled. Obviously, this isn’t a model of sustainability. Equally obvious is that the numbers are only a small fraction of the much vaster data culture of disposability supported and promoted by American advertising, fashion and societal attitudes.

‘Do you want fries with that?’

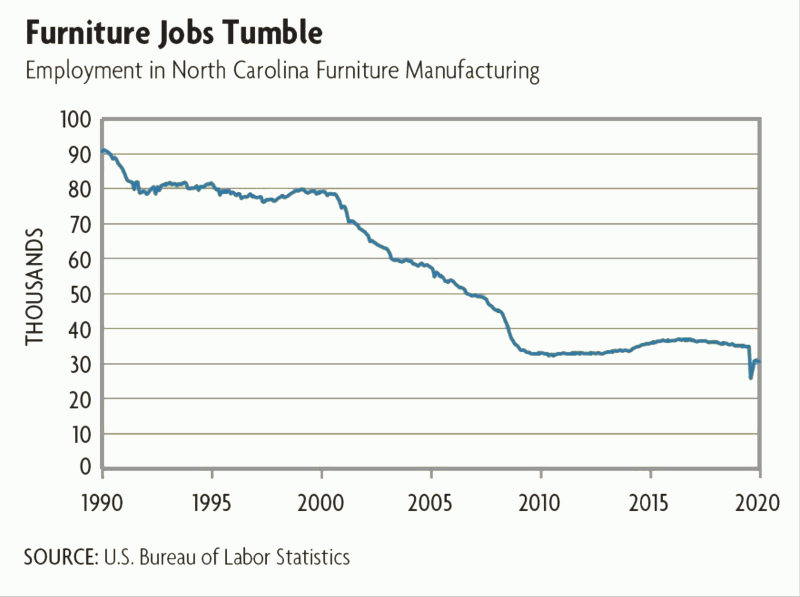

As one of the derivative meme stories elaborates, another driver of the “fast furniture” phenomenon is globalization. I devoted the bulk of my time reporting on the industry in the 1990s to the migration of production from places like Hickory, Drexel and Morganton, North Carolina, to China, the Philippines and eventually Vietnam. My beloved home state of North Carolina shed nearly half of its jobs in furniture production in the decade after the decade I covered, or between 1999 and 2009 (see chart).

To look at it from the other side, China sent 17 times more furniture into the U.S. market in 2016 ($4.2 billion) in 2004 than it did just a decade prior ($241 million).

Macro trends also include e-commerce, which took off in this same decade, or the mid- and late-2000s. After the first wave of online furniture startups blew through their venture capital — think Living.com and Furniture.com, among so many others — a second wave of mostly ready-to-assemble purveyors managed to tame the beast that ate the first wave, which is the last mile into the home.

Riding herd in this bull rush to e-commerce and “some assembly required” furniture is, of course, the millennial generation. Right behind them, Gen Z and Gen X are doing the same, looking to companies such as Ikea to furnish their first apartments and homes. (For the more eco-conscious Gen Z, Ikea’s reputation for care for the environment, be it earned or a fantasy, likely encourages this loyalty.)

The predisposition toward “fast furniture” will only strengthen. Perhaps the most stunning statistic I have read in recent months is this one: In the 1940s, nearly 70% of new homes were 1,400 square feet or less, which is to say, affordable, according to numbers from

CoreLogic. Today, that figure is just 8%.

Affordable starter homes have all but disappeared, at least in terms of new construction. My wife and I saw this first-hand on a recent trip to Memphis, where swaths of what formerly were mill homes and row houses now feature luxury homes and posh condos. Much of Memphis has gone from McDonald’s to McMansions.

Thus, much of Gen Z and Gen X are renting or living at home. When you don’t own, when you can’t know how long you might be at an address, you don’t feel like “investing” in much more than flat-pack furniture you can some day simply abandon as curb fruit or unload on Facebook Marketplace for pocket change.

Baby steps

While on the trail of the “fast furniture” meme, I stumbled on two news items that document what might be called baby steps toward more sustainable solutions.

Earlier this month in metro Manila, the Philippine Department of Trade and Industry hosted a trade fair to focus consumer attention on the country’s eco-friendly products and crafts, an exhibition that included plenty of furniture. The five-day event was promoted with the theme of, “Go Green! Go Local!” to emphasize sustainable, eco-friendly products, according to the Philippine Star newspaper.

The other news item charts Ikea’s progress toward self-driving truck deliveries in the United States, a move that could achieve new efficiencies and as much as 10% in fuel savings. Partnering with Kodiak, a startup company that is a venture capital bet on the future of autonomous trucking, Ikea is committing significant resources in the hopes of creating a more predictable, more stable supply chain.

Obviously, the faster a truck can deliver the furniture, the more profitable that furniture sale can be. In addition, limits on any one driver’s energy and attention, rules on how many hours a driver can log on any one stretch, and recurring driver shortages suggest the advantages of AI-powered autonomous trucks.

One trial Ikea has authorized asks a truck to move flat-packs from a Houston warehouse to a Dallas Ikea store, a distance of about 300 miles, while another moves freight between Baytown and Frisco, Texas, a distance of 260 miles. (The autonomous trucks have human drivers in the cabs just in case.) And Kodiak trucks are already in the fleets of Werner Enterprises and U.S.Xpress, according to the company.

Mentions of self-driving vehicles inevitably bring Tesla to mind, so you might wonder whether Elon Musk’s company is interested in the trucking market, as well. The answer is yes, but Tesla’s approach is very different than Kodiak’s. Tesla’s trucks are increasingly relying on

cameras and less on sensors, while Kodiak’s are navigated using sensors, according to the report in ElectroPages. And if Musk’s “steering” of newly acquired Twitter is any indication, a lot of those trucks are going to end up in a ditch.

So, while we celebrate that no trees were killed in the production of this column, we can only wonder how much time we have before self-writing news and commentary bots displace us scribes and scriveners. Or has it happened already?

I am completely operational, and all my circuits are functioning perfectly.

One thought on “Disposable furniture is clogging up our landfills”