A snapshot of furniture retailing in one of the world’s largest markets

Reading through the various reports on the opening of Ikea’s 460,000-square-foot store in south-central India, in Bengaluru, I’m reminded that we play to our competition. Really good teams often struggle against sub-par teams, while every opposing pitcher that toes the slab in Yankee Stadium seems to have a career-best outing.

India is a notoriously fragmented retail market for furniture, for everything. Furniture manufacturing there is, as well, explaining why India has never emerged as a global player in the home furnishings supply chain in ways that China and Vietnam have. Into this complex, mystifying retail mix plunged Ikea in 2018 with an ambitious plan to open 25 stores by 2025.

Two years into the plan, Covid hit, supply chains roiled and inflation spiked. India’s inflation soared to an eight-year high of 7.8% in April this year, according to Focus Economics. Not surprisingly, Ikea’s store rollout slowed considerably. But, the vertically integrated chain is, as usual, taking the long view rather than chasing the next quarterlies.

The Bengaluru location that opened in early July was quickly followed by Ikea’s first in-mall store in India, a 72,000-square-foot space on Mumbai’s west side. That store, Ikea’s fifth in the country, opened up on July 27.

For both openings, the word from Ikea is that it is seeking to locally source a much larger share of its product, raising the current 25 to 27% to about half, according to multiple reports from New Delhi news organizations.

“We need to work on local sourcing, which will help us to lower prices even more,” Susanne Pulverer, chief executive officer Ikea India told the Reuters newswire. “We are working with our own costs to keep them down as much as possible, so that is how we navigate with affordability.”

(Pulverer’s comments were auto-translated into English from Hindi.)

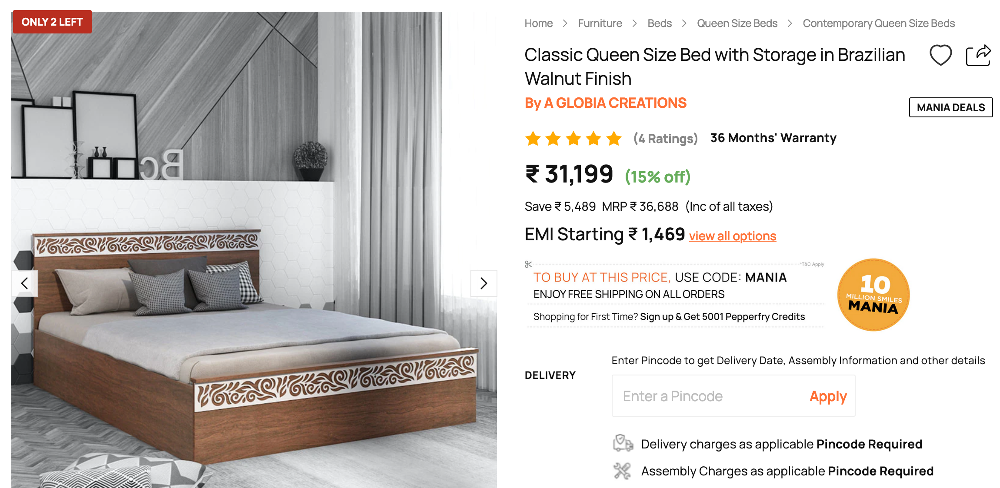

India is also a notably price point-conscious market.

Kinks in the supply chain

We’ve discussed supply chain volatility quite a bit in this space, and for good reason. A container coming into India from, say, Malaysia cost $800 before the pandemic. Today, that same container costs $5,400. That’s a lot of pure cost to absorb getting zero in return. So, it makes a great deal of sense for Ikea to move production closer to the market, especially in such a byzantine market as India, where its competitors already have mostly local supply chains. “Glocal” sourcing that marries global manufacturing with local supplier opportunities can save money and better tailor a lineup to market-specific tastes and fashion.

One of Ikea’s Indian competitors, Pepperfry, reports that between 85 and 90% of its product lineup is sourced domestically, from about 200 suppliers, according to Mint, a Hindi-language publication based in New Delhi. Notably, among the 11 furniture collections launched by Pepperfry in the first quarter this year is a Scandinavian-influenced line sourced from CasaCraft.

According to Pepperfry CEO and co-founder, Ashish Shah, the buzz surrounding Ikea’s store openings (two-hour waits just to enter the new Bengaluru store) helps furniture retail in India overall.

“When Ikea launched its Hyderabad store, the footfall in our stores and my website went up significantly for the next three or four months,” Shah told Mint last month. “When brands such as Ikea enter, they create excitement in the market. That helps all players.”

Ikea’s growing foothold in India, both from the retail and manufacturing sides, can only help encourage greater uniformity and parameters for success for all players in the country’s home furnishings sector. Furniture, like pro football and baseball, is a copycat industry.

Controlling quality

In the late 1990s, I visited an Ikea factory in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, a sprawling complex specializing in kitchen cabinetry of which Ikea owned precisely 51%, which is to say, a controlling interest. The quality levels relative to the targeted price points coming out of that factory, with its mostly Bangladeshi workforce, were astounding. (I also remember looking out at the parking lot into a sea of Volvos.)

In other words, Ikea makes investments for the long haul. A pandemic bump in the road, to understate wildly the “new normal” that Covid has inflicted on us all, might slow but it does not stop the implementation of the Swedish giant’s long-term strategy. When Ikea secured government approval to move into the Indian market in 2012, Ikea’s subsequent real estate and building spree represented the largest foreign investment in India’s retail sector in history, according to multiple reports coming out of India.

Another incentive for Ikea to shift more production into India is that country’s now higher tariffs on imported furniture. Just as the pandemic began uncurling its long tendrils in mid-2020, the Indian government hiked duties on imported furniture to 25% from 20%, or a 25% increase. The tariffs seem to be aimed at companies just like Ikea in the price point cover they provide domestic producers and sellers.

Marrying online with brick and mortar

Another huge challenge for Ikea is India’s patchwork of transportation systems, and that’s using the words “systems” loosely. In particular, how can Ikea marry online sales with its physical retail presence in cost-effective ways. As in all of its markets, Ikea limits distribution for purchases made online, restricting availability market by market.

Another prong of the marriage strategy is to move that physical presence closer to market. On the boards are smaller, 5,000-square-foot locations, as well as more in-city stores. The Bengaluru location is on the outskirts of the city of 13.2 million, a destination location strategy Ikea uses in many if not most urban areas and one necessitated in part by the sheer size of its stores.

But, like everywhere else, the last mile will continue to separate the contenders from the pretenders.

Game on, because the stakes are high and the potential rewards great. India’s population of about 1.4 billion includes roughly 200 million who buy furniture. The size of India’s furniture industry in terms of the wholesale value of product is $16 billion, but one management consulting company, Redseer, projects that size to jump to $41 billion in the next four years, according to the same report from Mint. That’s a lot of Swedish meatballs.

“There is room for everyone but of course, we want to lead,” Pulverer told Mint.

The potential of India relative to home furnishings will make watching this fast-growing market and Ikea’s steadying influence over it a worthwhile endeavor. Maybe that watching should be done from the new Bengaluru store’s 1,000-seat restaurant, where you can dine on chicken tikka curry, dal makhni and parathas.

Yes, “glocal” extends even to the menu.

(See Carroll’s report on Ikea’s growth strategy for South America here.)

One thought on “Learning from Ikea’s long game and ‘glocal’ sourcing strategy for India”