Domestic producers have targeted more than 20 countries that produce mattresses since the first petition was filed before the pandemic

HIGH POINT — For years, Vietnam bedroom furniture manufacturers were concerned that an antidumping case from the U.S. would arrive on their shores and threaten an industry that had become one of the most important segments of its manufacturing base.

The concern was valid not just because of the amount of bedroom that shifted there from China following the early 2005 imposition of duties on Chinese-made wooden bedroom — the largest producers also were many of the same Chinese- and Taiwanese-based companies hit with duties in China that shifted their manufacturing to Vietnam. Of course, many were nervous.

Combined with the output of locally owned and managed Vietnamese furniture plants, wood furniture became a major export that included not only bedroom, but also dining, occasional, home entertainment and even home office furniture.

According to figures from investment banking firm Mann, Armistead & Epperson, wood furniture imports from Vietnam have skyrocketed in the past decade, climbing from $1.7 billion in 2012 to $5.7 billion in 2021. This outpaced exports in the category from China, where shipments of wood bedroom furniture totaled $2.7 billion in 2021, down from $5.7 billion in 2018.

Some of the shift more recently also had to do with China tariffs which also raised the prices on a wide mix of consumer goods, not just furniture.

Thus, producers in Vietnam — Chinese, Taiwanese and Vietnamese alike — became significant competitors for domestic producers that brought the original antidumping case against China.

Yet duties on wooden bedroom furniture remained focused on China, whose rising costs ultimately would have shifted production to lower-cost countries regardless of antidumping. In addition to Vietnam, wood furniture shipments have also risen from Malaysia, Mexico, Indonesia, India, Poland and even Brazil, although none of these countries come close to shipments from China and Vietnam.

Fast forward to antidumping in the bedding industry, which surfaced again in late July with a third investigation into alleged dumping of mattresses into the U.S. market. At the heart of this is alleged unfair pricing from foreign producers that petitioners say has injured the domestic industry in terms of job losses and related financial harm that has contributed to such job losses.

As many recall, antidumping in the bedding industry started with a pre-pandemic investigation that initially focused on China. This resulted in a first round of dumping margins in 2019 ranging from 57.03% to 1,731.75% on Chinese-made mattresses.

As production shifted from China, domestic producers put the spotlight on other countries in a second-round investigation that included Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Serbia, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam. A year later, they too were hit with duties that ranged from a low of 2% coming out of Indonesia to a high of 763.28% on mattresses shipped from Thailand.

In its final determination, the Department of Commerce also assessed a final countervailing subsidy margin of 97.78% on all mattress imports from China. (Antidumping duties address unfair pricing tactics of producers, while countervailing duties address allegations of government subsidization of foreign producers, which also happens all the time in the U.S. thanks to incentives and other tax breaks tied to job creation.)

“Chinese imports declined and were supplanted by subject imports from other country sources,” states the latest petition filed July 28 with the International Trade Commission and the Department of Commerce. “Indeed, many of the same Chinese-based firms that had supplied the U.S. market from production facilities in China began to export mattresses to the United States from related production facilities in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Serbia, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam.”

The third-round petition alleges further “country hopping” to nations that include Bosnia, Bulgaria, Burma, India, Indonesia, Italy, Kosovo, Mexico, the Philippines, Poland, Slovenia, Spain and Taiwan. In some cases such as Italy, the shipments to the U.S. are small, while in others such as Mexico, they are more significant.

But the latest petition also begs the question about what defines unfair pricing.

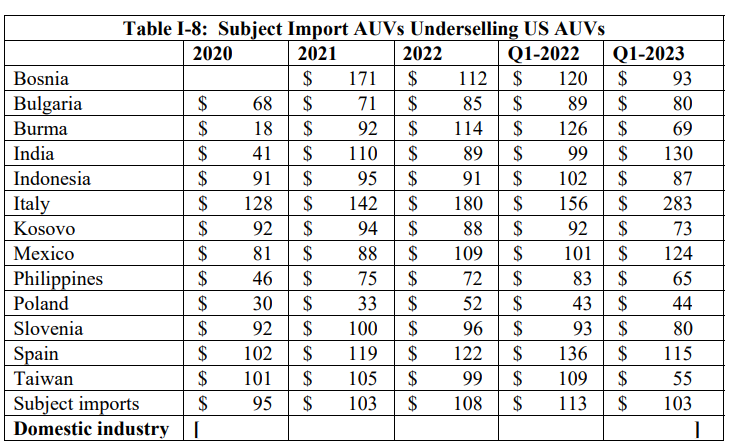

The chart below may help explain this to a degree, although it leaves out the pricing of domestic producers.

commercial U.S. shipments compared with the AUVs for subject imports indicates pervasive underselling by

imports from the individual subject countries. The petition goes on to state that AUVs for

subject imports were less than half of the AUVs for the domestic industry’s U.S. shipments.

In the wood bedroom case, a main argument was that bedrooms produced in China were selling into the U.S. market below materials costs, a violation of international trade laws. The domestic producers in that case too demonstrated how such pricing tactics were resulting in injury to the industry, namely widespread job losses.

The latest bedding petition talks a lot about materials in terms of how bedding products are made. But at least in the public version of the petition, materials costs don’t appear to be a major driving factor in the dispute, only the fact that prices are significantly lower, and thus unfair. Details of this will likely emerge in the coming months as the government’s investigation continues.

And like the bedroom case, the petition alleges that unfair pricing tactics have resulted in injury to the bedding industry including job losses. The proof of such injury will be a major factor in whether the government decides to apply duties to additional countries named in the latest bedding petition that are assigned to manufacturers but paid by importers of record.

The bedding segment may be different, but the furniture industry has always pursued lower-cost labor, whether it was moving from New England to Michigan, from Michigan to North Carolina, from North Carolina to Taiwan, from Taiwan to mainland China, from China to Vietnam and so on.

Note that most promotional to lower middle priced upholstery also continues to be made in Mississippi, another low cost area in terms of labor. Obviously this quest to find the lowest-cost labor helps lower product pricing, as labor along with materials are among the biggest expenses of any factory.

But here is a key difference between the wooden bedroom furniture and the bedding cases: In the wooden bedroom furniture case, the domestic manufacturers limited their antidumping petition to China.

Perhaps they realized that not only would other petitions against countries like Vietnam be futile in halting global trade, which ultimately produces competitive pricing for consumers. They also believed it would further divide an industry that went through a civil war during the initial antidumping debate that pitted importers and retailers against the domestic petitioners.

In the end, the issue ultimately gets down to competition and, of course, fair pricing.

We believe price competition exists in the bedding industry as well — even among domestic manufacturers, who likely do their best to undercut their competition at every chance possible. After all, they are working with retailers, some of which have been known to switch suppliers just to save a few dollars on a single SKU.

Ultimately the government will determine whether the alleged unfair pricing in this latest petition has resulted in material injury that warrants duties on these other countries.

But in the end, the definition of fair or unfair pricing is really not up to the government or the domestic manufacturers — many of which likely have huge legacy costs running their businesses. It’s up to consumers buying their product.

For the domestic industry’s sake, let’s hope that fair pricing doesn’t mean stifling competition, or pricing themselves out of the market. Retailers and consumers will always find a better deal somewhere.

.jpg)